Genetic testing. Language development at two. Stimulant medication shortage.

Greetings! It has been a while. Growing work and family obligations have kept pushing back this next installment of DBP in 1-2-3. Better late than never. With this installment, I’m bringing back Child Development 101 and venting a bit on the nationwide shortage of stimulant medications. For new readers, DBP in 1-2-3 is a newsletter devoted to child development and behavior from a medical perspective. I hope you find value in reading it as I do writing it.

Thanks again for stopping by, and feel free to send me any questions or provide comments below.

#1 Genetic Testing

According to the American College of Medical Genetics, genetic testing should always be considered for any child diagnosed with developmental delay, autism, and intellectual disability, even in the primary care setting. It is estimated that genetics can explain up to 15% of children diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD). While the probability of a positive finding is still low, genetic testing should not be overlooked. This is analogous to an audiology evaluation in children with speech or language delay; most will have normal hearing. However, it is essential to rule out hearing loss, as early intervention can lead to good long-term outcomes.

Genetic testing may not provide a cure or novel treatment for a child with an NDD, but it offers much value to clinicians and families. First, it can explain the child’s developmental delay or disability, providing closure to the family and preventing unnecessary testing, evaluations, and procedures. A positive finding can also allow the family to seek genetic counseling regarding heritability and recurrence rate, especially if they are considering more children.

A genetic diagnosis can clarify the prognosis, expected clinical course, and information about treatment, symptom management, and surveillance for known complications. It may also open opportunities for the child to join research protocols and family support groups or organizations.

The baseline testing in our specialty clinic, Fragile X DNA analysis and chromosomal microarray (CMA), are also reasonable to provide in the primary care setting. High-resolution chromosomal analysis is still available but is no longer recommended as first-tier testing unless a balanced translocation is suspected (which is very rare).

I like to use the analogy of an encyclopedia library with families to explain genetic testing (though it makes me sound outdated). CMA checks if the child has 46 chromosomes (number of books in the encyclopedia), 23 from the mother and 23 from the father. The test also looks at the book chapters to see if any missing or duplicated chapters exist. These are called “copy number variants.” CMA can identify hundreds of microdeletions or microduplications that cannot be seen on chromosomal analysis. CMA is not looking for specific genes (grammatical or spelling errors in the sentences). That’s where whole exome or genome sequencing comes in.

Fragile X testing specifically looks for CGG trinucleotide repeats of the FMR1 gene in the X-chromosome. Fragile X is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability and is highly co-occurring with autism. Therefore, fragile X testing is recommended for any child with global developmental delay, intellectual disability, or autism. Of course, suspicion is higher if the child has physical features commonly associated with Fragile X, such as prominent ears, elongated facies, and a high-arched palate.

Whole exome (WES) or genome sequencing is used to identify specific gene mutations associated with an NDD. It is a higher resolution genetic test. Therefore, the probability of a positive finding for a molecular diagnosis increases to about 30%. It is essential to know that the likelihood of finding variants of uncertain significance (VUS) or some unrelated but clinically relevant finding is higher in exome sequencing (e.g., risk for cancer). Families should always discuss the results of WES with a genetic counselor or medical geneticist. They can help interpret the results and provide appropriate counseling for the family.

Many families are hesitant to pursue genetic testing because it involves a blood draw in a child who may have severe behavioral challenges. Fortunately, the availability of buccal swab versions of these tests is increasing. Genetic testing should be discussed and offered to any family with a child with ASD and global developmental delay. The more severe the condition, the more likely an identifiable molecular cause is.

Genetic testing in NDD is a much bigger topic to cover in just a newsletter. There are a lot of excellent resources out there. Here are a few to keep in mind for families interested in genetic testing for developmental delay.

#2 Language Leaps and Bounds

The age range of 2-3 years is a critical period for language development in children. Some children may start speaking earlier or later during this time, and their language abilities may fluctuate. There is often a “burst” of speech at this age, with parents saying it seemed like their child started talking overnight. By the age of 3, most children should have 200+ words (“too many to count”) and be able to combine them in 2-4 word sentences in unique ways to express original thoughts, ask questions and engage in a few back-and-forth exchanges. Additionally, children should be able to use pronouns and understand propositions (e.g., “put the ball under the chair”).

Further assessment (including one by an audiologist) and early intervention are necessary if a child is not attempting to talk, babble, or follow 1-step commands by this age. It is important to note that gestures are essential in language and cognitive development. Children who use a lot of gesturing are likely to develop specific language skills even if they are delayed with speech. Therefore, it is crucial to look for gestures during your encounter with a 2-3-year-old, such as waving bye-bye, high fives, fist bumps, moving a toy car back and forth, and rubbing their belly to indicate they want food.

In this age range, children should demonstrate a lot of variation in speech, including modifiers, early grammar, and some possessives. In addition, children should be communicating through speech and not just using speech to label objects or express themselves. Although errors are common in this age range, the intent to communicate with speech should be obvious.

Children at this age are expected to communicate easily with family members but may have more difficulty with strangers. It should raise a red flag if a child mostly imitates speech by echoing or scripting. Social interaction and play are crucial for language development, as speech does not occur in a vacuum or simply through imitation. That’s why videos promoting enhancing or bolstering a child’s language development are fraudulent. Research has shown that children who are mostly exposed to speech through screens or hear very little speech from their loved ones are at significant risk for language delay.

Language delay in this age range is a risk factor for verbal-based learning disabilities or cognitive impairments down the road, as language development is intricately tied with cognitive development and functional level. It is estimated that more than 40% of children with early language delays have learning problems in school. Although research has shown that significant language delay is not tied to bilingualism or the male gender, there may be a slight lag or subtle delay.

Parents can get guidance on promoting language development in their toddlers by utilizing public domain resources such as the CDC and Zero to Three. In addition, a wealth of great books about language development are available for parents. Finally, daily reading and social play allow children to hear and practice speech.

It can be challenging to evaluate language development in the office since parent recall is unreliable, and children are unlikely to act or behave as they would at home. Videos may be helpful, but it is best to document what the child is saying now at each encounter. I often like to stand by the door and see if I can hear the child talk with just the parent in the room. Other strategies to consider are asking office staff to listen to the child talk while they are checked in, measured, and taking their vital signs. During an exam, try to give the child 1-step instructions without gestures (keeping your hands in your pockets is an excellent way to prevent yourself from using gestures) and give 2-step commands, like “take off your shoes and stand by the door,” a try. Having some simple toys and books in the room could be valuable in prompting speech. It may be due to shyness or anxiety if children ignore or avoid you or look confused, but it could also mean they have trouble with receptive language. Keep an eye out for the parent doing a lot of scaffolding or speaking for the child. It may indicate that the child is not communicating at their expected level.

#3 ADHD Medication shortage

I had previously planned to write about early intervention services for children under three with developmental delays. However, a topic too pertinent to ignore is the nationwide shortage of stimulant medications in the United States.1 I feel your pain if you manage a lot of ADHD in your practice. Not a day goes by without me getting several calls or messages from frantic families reporting that their pharmacy is out of stock of their child’s stimulant medication.

There are two primary reasons for this shortage: 1) an uptick in ADHD diagnoses over the last couple of years and, therefore, greater demand for these medications, and 2) DEA quotas on stimulant medications because of their controlled-substance status. Insurance and pharmacy restrictions make it even more challenging for families to get a hold of these medications. For instance, name brands may be in stock but are way too expensive for families to purchase because it is not covered under their insurance plan. Many pharmacies also are unwilling to share information with families about the availability of stimulants because of concern for diversion. Short-staffed medical offices and pharmacies have only exacerbated the problem. These factors have led to high frustration for patients and healthcare providers alike. Children with ADHD who get real functional benefits from these medications are the ones who suffer the most. I’ve seen families ration their stash of stimulants by giving them to the child only on school days or halving the dose to make the prescription last longer. It’s simply unfair to these children.

You could consider several strategies to manage things while we ride the shortage out (I’m told it will end in April, but with so many moving pieces and the uncertainty of the supply chains, who knows?)

Try an alternative stimulant. Take Adderall, for example, which seems to be getting the most press of all the stimulants in shortage. However, there are other types of stimulants similar to Adderall, like Vyvanse and Dexedrine, that should work equally well though there may be some minor differences, such as how long it takes before it starts working and the duration of the day.

You could also prescribe an immediate-release stimulant if extended-release versions are out of stock. It might mean the patient has to take it 2-3 times per day, but this may work out fine in the short term.

Consider the other type of stimulant. For instance, if Adderall (an amphetamine derivative) is unavailable, you could switch to a methylphenidate-based stimulant like Concerta or Focalin XR. About 50% of children with ADHD respond equally well to both. But, again, all this will also hinge on whether the family’s insurance plan covers these alternatives. Many are still unavailable in generic form, so the insurance could deny them or be considerably more expensive. I’ve seen some insurance make accommodations because of the shortage but may need a letter from the prescribing clinician.

The ADHD Medication Guide is a terrific resource to see your ADHD medication options on two pages. The way it’s presented also makes it easy to convert dosing from one drug to another. For instance, 18 mg of Concerta is equivalent to 10 mg of Ritalin LA, and 10 mg of Adderall XR equals 30 mg of Vyvanse. Highly recommend having a copy near your workstation (I have it easily accessible as a PDF on my various digital devices) or in your exam rooms.

Consider a nonstimulant. It may not be ideal if the child is doing well on stimulant medication, but likely to be readily available. The most commonly prescribed nonstimulants are atomoxetine (Strattera) and guanfacine (Intuniv for the extended-release version). I’ve written about nonstimulant medications in the past. They are not as effective as stimulants, but they have some advantages.

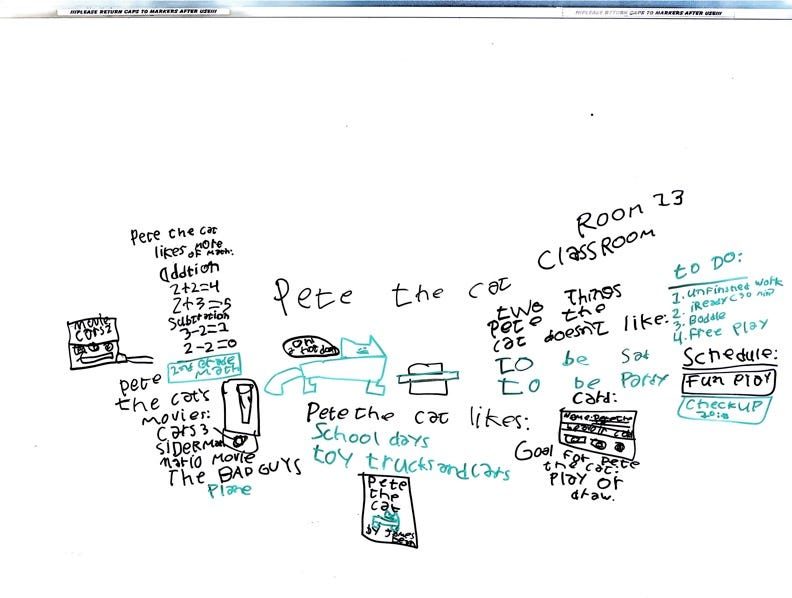

Lastly, consider leveraging nonpharmacological tools or interventions like parent behavior training, regular cardiovascular exercise, and incorporating structure and routines in the child’s day-to-day activities. Many children with ADHD thrive with visual reminders, rewards/incentives, and schedules. Finally, don’t forget what the school can do to support children with ADHD. They can succeed in the classroom with accommodations and modifications, especially with a formal 504 Plan or IEP.