Neurobehavioral status exam. Melatonin. Selective Mutism.

Welcome to another installment of DBP in 1-2-3! Thanks for reading and feel free to ask questions or provide comments below.

#1 Neurobehavioral status exam

Concerns about learning, attentional, and executive functioning skills are common in childhood. They often emerge in grade school, usually between the ages of 6-8 years, when academic demands increase significantly and expectations for children to be more independent with adaptive skills (e.g., personal hygiene). This is the age range when a diagnosis of a learning disorder like dyslexia or ADHD is suspected because children with these disabilities really start to stand out compared to their peers.

While making a neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosis is often beyond the scope of most general pediatric providers and often requires expanded psychological testing or assessment, there are several activities and procedures one can accomplish in a reasonable amount of time in a busy primary care practice. I’ve mentioned in a prior newsletter that a good history is most important in narrowing a differential diagnosis. Using validated behavioral rating scales (i.e., the Vanderbilt) certainly helps. I have also written about some activities providers can have children do in the office that may elicit red flags for dyslexia. There are also some quick and easy activities to administer that can give you insight into a child’s executive functioning skills. They can be incorporated in the physical exam and add no more than ten minutes to the visit. Understandably that could be quite significant in a busy primary care office, but doing these activities may be more worthwhile than a physical exam, especially if the child is a well-established patient and has an otherwise benign medical history.

In the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics, we often call this the neurobehavioral status exam. It's really a set of semi-structured exercises or activities that allow you to see how well children pay attention, self-regulate, organize their thoughts and access their working memory. Here are a few examples:

To assess reading fluency and comprehension, ask the child to read a paragraph appropriate for age. As a rough guide, children should be able to identify letters and letter groups by kindergarten, read simple words by first grade, read word clusters and phrases by second grade, read and comprehend sentences by the third grade and read whole paragraphs fluently by the fourth grade.

To assess oral expression, memory or sequencing, have the child tell you about a show or movie they have seen recently, or have them explain to you how to play one of their favorite video games.

To assess fine motor and visual-spatial skills, have the child draw a person (I will discuss how to analyze this drawing in a future newsletter). Having the child write a few sentences can also give you insight into their fine motor skills and written expression and language processing skills. For example, I like to ask children to write a few sentences about a recent vacation or what they did over the weekend.

To assess short-term memory and sequencing, ask the child to repeat a series of random numbers (rough norms are age minus one from 5-10 years of age, so a typical 5-year old should be able to repeat 4 digits).

To assess auditory processing, give the child a multiple-step task to complete in the exact order given (rough norms are also age minus one from 5-10 years of age)

To assess impulse control, try left/right commands:

These are usually fun tasks for children to do in the office, and parents appreciate a clinician doing something more than just getting the history or having the parent/teacher fill out a survey. It is not necessary to do all of them. Instead, I would pick and choose what makes the most sense at the visit. Perhaps start with one or two. Usually, the history will help you decide which ones to try first. Here is a worksheet I keep handy in the office to provide some structure and keep notes during the neurobehavioral status exam. Feel free to use and modify to your liking.

All of these activities come from subtests in standardized psychological tests like the Weschler and Stanford Binet). While they are not administered in a standardized manner in this context (there are no scores or percentiles), it will give you a decent impression of how concerned you should be for a neurodevelopmental disorder. I’ve often diagnosed ADHD from these activities because the child’s working memory or impulse control difficulties were so obvious on the neurobehavioral status exam.

#2 Melatonin

Sleep problems are prevalent in pediatrics. Most, if not all, pediatric providers have a spiel or two about proper sleep hygiene and strategies to promote good sleep in children, along with a cookie cutter handout for families to take home at the end of the visit. There are dozens of books and websites out there that promise fail-safe solutions for problems like curtain calls and frequent awakenings at night. I probably see more sleep problems than the typical pediatrician, given that disordered sleep is strongly associated with developmental delay or disability. There is a special place in my heart for the severely autistic child who cannot sleep more than a few hours at night without waking up the whole house. While implementing behavioral strategies is a must to sustain healthy sleep in children, medication is something all providers should consider, at least as a short-term solution so everyone in the house can get some decent sleep. Perhaps one day, I will write about some of these prescribed medications, like clonidine, trazodone, and atypical antipsychotics. I generally stay away from benzodiazepines because they can really backfire. Diphenhydramine (aka Benadryl) is a common over-the-counter drug used to help a child sleep. I prescribed it all the time as a resident in the hospital wards. I generally avoid recommending it today because it often leads to grogginess in the morning and sometimes causes a paradoxical effect (i.e., the child becomes activated). What is becoming more and more popular these days is melatonin.

It's unclear how common melatonin is being used presently, but sales figures suggest that it is rapidly on the rise. I see this on the front lines of my practice, and I presume my colleagues in general pediatrics do as well. Because it is a dietary supplement and does not need a prescription (interestingly, one needs a prescription for melatonin in other countries), many families give melatonin to their children without consulting their doctor. There are all sorts of advice and information about using melatonin over the internet and in parent chat groups or forums. It is not unusual for a patient with ADHD or autism to take melatonin, sometimes doses as high as 10 mg. Melatonin is widely available in grocery and vitamin stores. Its availability in a gummy formulation says it all about the ubiquity of melatonin and its marketing for children. I have never seen major adverse side effects in my patients who have taken melatonin. Occasionally, there are milder side effects like generalized headaches and stomachaches, and enuresis. What is hard for me to inform families is 1) how well it works and 2) if there are any long-term adverse side effects from melatonin. We don't think so, but robust clinical trials have not yet been done to say with a high degree of confidence. A few studies on children with autism and ADHD show promising effects on helping children fall asleep more quickly. That's not surprising, knowing how melatonin works in our body as a naturally produced hormone from the pineal gland. It primarily functions as a chronobiotic agent that regulates our circadian rhythms. Our body's levels increase as it gets closer to bedtime and decrease in the morning before we awaken. For some individuals, melatonin can have hypnotic effects. The overall goal of giving melatonin to children is to help them fall asleep sooner and, as a result, get more total sleep time throughout the night.

I typically recommend a starting dose of 0.5-1 mg. Most do not need more than that, but it's not unusual to see a child on 3-6 mg. Even the lowest dose of melatonin is substantially more than what the pineal gland typically makes. I often tell families to give the melatonin 30-60 minutes before bedtime, but that's not based on any supporting studies. Melatonin levels actually start to rise 1-3 hours before sleep, so it may make more sense to give the melatonin even earlier in the evening. In my experience, however, that's not ideal because of melatonin's potential hypnotic effect. I also recommend families to choose pure melatonin, not formulations mixed with other ingredients, such as L-carnitine and ginkgo balboa, to promote other benefits like improved attention/focus, mood, impulse control.

Here’s a terrific article that was recently published in the New York Times about melatonin.

#3 Selective Mutism

Selective mutism (SM) is one of the more gratifying diagnoses I make in my practice. For one, the diagnostic criteria from the DSM-5 are pretty clear cut compared to other disorders like autism, where there is a lot more room for interpretation (how repetitive does a repetitive behavior have to be to qualify for a diagnosis?). With SM, children have this “consistent failure to speak in specific social situations in which there is an expectation for speaking despite speaking in other situations.” The most common situation in children by far is school but, it is not unusual for children with SM to not speak at a family friend or relative’s house or the doctor’s office.

SM is rare in the general population, with an estimated prevalence of 1%. Children with SM can be misdiagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder or oppositional defiant disorder. Most are brushed off as shy or anxious. Families are often told there is nothing wrong with the child and that she will “grow out of it.” SM is, however, one of those diagnoses where once you see it, you’ll realize how distinguishable it is from other disorders. You can do a few key activities in a clinical encounter to cinch the diagnosis besides getting a good history. When I suspect SM, I like to leave the room and eavesdrop at the door. Generally, children with SM will start talking to the parent while I am out of the room. Sometimes they will become profoundly chatty. When I reenter the room, silence. I also ask families to show me a video or two of the child talking at home. These days, most families have something ready to show on their phones. They are baffled when they are told by someone, like a teacher, that their child does not talk.

To be clear, children with SM do not have to be completely mute to qualify for an SM diagnosis. They have to talk significantly less than expected for their age, which interferes with their ability to learn, participate, and perform. I have some patients who will talk in school, but teachers will say, “she whispers all the time,” or they really need a lot of encouragement to talk, but even then, it’s significantly less than their peers. It’s important to think of SM as a communication disorder. It goes beyond just being shy or anxious around people. Children with SM are not intentionally refusing to speak. Many had a history of a speech or language delay when they were younger, but they do not usually have severe deficits in speech production. This points to the other criteria for an SM diagnosis: “The failure to speak is not attributable to a lack of knowledge of, or comfort with, the spoken language required in the social situation.”

SM often gets confused with social phobia, which is characterized by excessive embarrassment and extreme shyness in novel situations, accompanied by avoidance behavior. Children with social phobia tend to avoid locations and anxiety-provoking situations and more varied and less limited than in selective mutism.

The prognosis of SM depends on many variables, but experts generally agree that early intervention usually results in better outcomes. Treatment focuses on two components: 1) addressing the anxiety around social interactions and 2) treating the social communication disorder. For most cases, this involves a child psychologist or therapist and a speech-language pathologist. Combined treatment using behavioral strategies and linguistic-based activities can help children be more comfortable speaking in certain settings and promote appropriate pragmatic language development. I’ve been a developmental-behavioral pediatrician long enough to follow a handful of children with SM for years, some now in their teens. While all have made progress, they all continue to have some anxiety around social situations and are on the quiet side at school. I have a couple of patients who get considerable benefit from an SSRI medication to target symptoms of anxiety. Unfortunately, longitudinal studies are lacking in SM. Some experts caution that these children are at very high risk for anxiety and/or mood disorders and continue to struggle as adults. Not surprisingly, there is often a strong family history of anxiety.

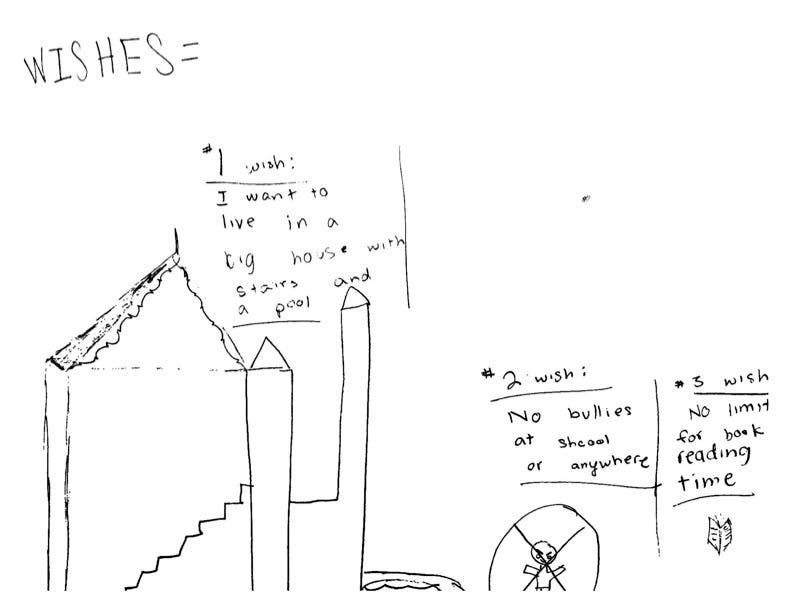

Thanks for reading. As always, I like to end the newsletter with a drawing from one of my patients. An 8-year-old boy drew this picture. When he saw me, he was bullied at school, leading to a high degree of anxiety and behavioral outbursts. An introvert by nature, he preferred activities like reading and drawing over group activities. Perhaps his number one wish to live in a more spacious home reflects that inclination for a solitary existence.